Gardens of Light

Of rebirth and the ghosts of memories

I think about old images a lot, more than I should I suppose—about Super 8 and Brownies and VCRs and slides. Everyone has them. Somewhere, in some family member’s dark, old attic, there is a box of pictures of people you, mostly, don’t know.

Years ago, long before the miracle of digital, as I was cleaning out my father’s house—the house where I grew up—I stumbled upon an enormous box of dusty and decaying color slides. They were my mother’s, thousands of them, all neatly labeled and mostly dated. They were from the mid-1950s, before she met my father. For years, she took long, cruiseship-style voyages to Europe, a single woman sailing the ocean blue to visit the Roman Coliseum and the Dickens’ Old Curiosity Shop.

I knew she took those trips because I had her diaries. But I hadn’t seen the pictures until I held them in my hands that day at my father’s. A treasure trove. Priceless. Now that I have the technology at my fingertips to scan those slides, I’ve slowly been working my way through them, showing my daughter little snippets in her grandmother’s life.

“Was your mommy a princess?” Little Bean asked about one picture in particular that showed my mother as a bridesmaid in a pink chiffon, ruffled dress.

But in many pictures, when my daughter asked, “Who is that?”

I had no idea.

All that light being imprinted, all those ghosts of my parents’ past, just sitting there, nameless, caught in a split second of a split second. Who was the photographer behind those blurry images of my mom standing in front of a trellis in Paris? Who was the grinning man in a short tie, holding a poodle on some street in Amsterdam?

Why would my mother take a picture of that particular street sign?

Or that building? Who was she before she was my mom?

I thought of this as I took pictures of my small family while we strolled around our yard, doing a little pre-spring inspection of the soil, the fence, the grass—our tiny urban plot there behind our house. These were small flashes of living as we prepared our home for its own rebirth.

I considered where those pictures would end up. Who is going to stumble upon an old flash drive in a junk store in 50 years and then go find some old ASUS computer to scan through images of me with my baby?

Just doing normal stuff. Just living.

What will they think of me, based on the chilly blue of a near-spring day in our earthen lot in some unknown place? Will they be able to see how much I love my family from the pictures I take? Will we look happy?

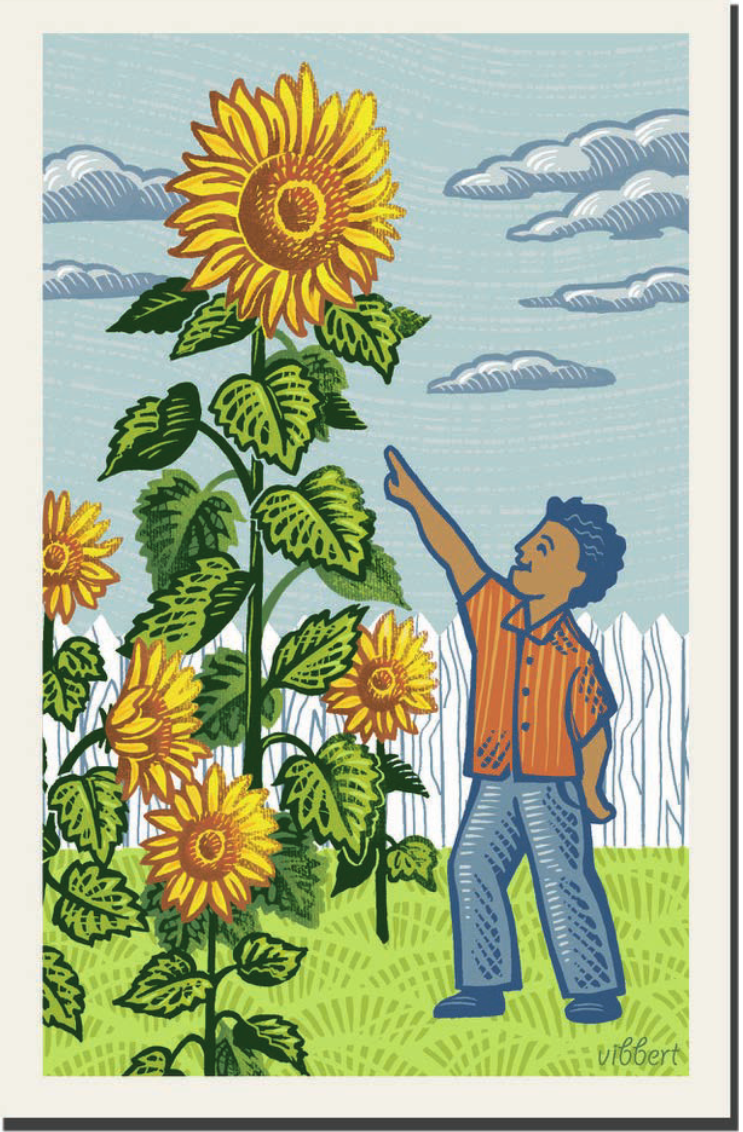

There is a picture of me, maybe 4 or 5 years old, standing in my backyard, in my mother’s garden, under an enormous sunflower. I’m grinning and pointing up at the yellow head of the flower. I’m happy.

I’m happy because it’s my yard.

And because my mother is taking the picture. And because my father will be home soon. And because it’s a sunny day. And because maybe, there is a grilled cheese sandwich waiting for me. To ghost me, looking at this photo now, possibility is endless.

I look at the digital pictures of my own daughter in her own yard, and I see my smile. My anticipation. She picked some smooth stones out of the vegetable patch and held them up, and I took a picture of her. The stones shimmered in the sunlight.

Full circle. The technology is different, but the transformative power of the dirt isn’t. That’s the same.

We are all, someday, going to be shadows on glass, or digital dots, or grooves, or tape, just sitting there in our backyards, pointing up at our sunflowers or holding tiny stones.

Someday, all that will remain will be us, standing with our arm around someone we love in front of Cinderella’s castle or sweating with joy, leaning over the Mount Washington summit sign.

We grow, we die. We’re captured somewhere living, for just a moment. The methods change, but the heart remains. Just like the garden, our impermanence is our strength.

We are, in the end, just light. I think I’m fine with that.

BY DAN SZCZESNY | ILLUSTRATION BY CAROLYN VIBBERT