Once More, and Always, to the Lake

PEOPLE WHO SPEND A LOT OF TIME ON A LAKE—whether year-round or every summer or for just one much-anticipated week every year—tend to feel possessive about it. We talk about “our lake” and “our loons,” as though without us, these things wouldn’t exist. Lakes and loons don’t belong to people. We know that. What we possess are the moments we spend at the lake—moments we return to no matter how long it has been since we were there.

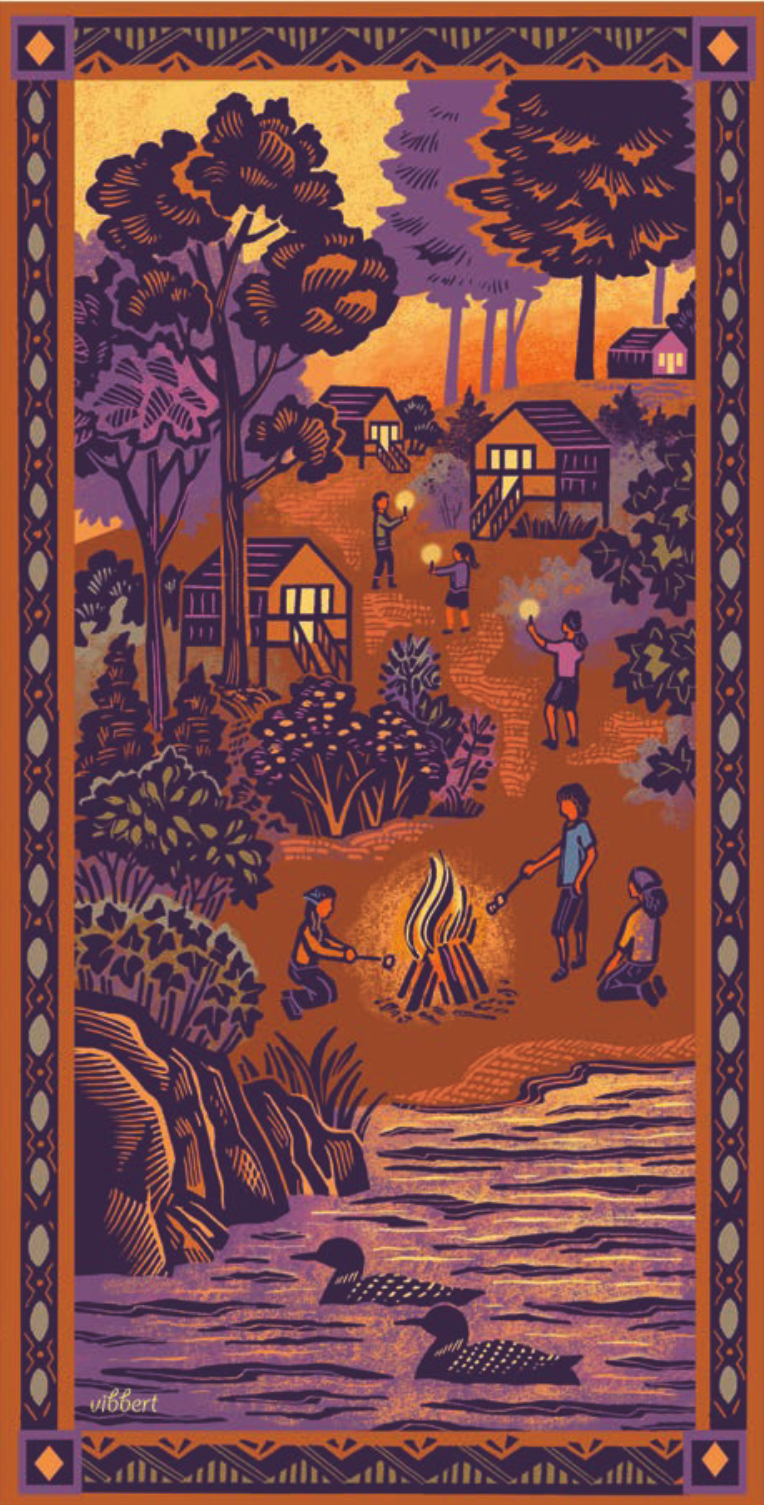

If you grew up on a lake, as I did, it’s where you learned to swim, skip stones and catch frogs. It’s where you learned to bait a hook, paddle a canoe, row a boat and slide a motorboat up to a dock. On the lakeshore, you learned to build a campfire, cut marshmallow sticks and make a s’more. You spent winter afternoons on the ice and trudged home to a warm house with a pair of skates slung over your shoulder.

As a boy, E.B. White spent every August at a rented camp on Belgrade Lake in Maine. Memories of these summers inspired one of his most famous essays, “Once More to the Lake.” The author of Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little describes returning to Belgrade Lake with his son and re-creating his childhood experience. He recalls the dragonfly that alit on the tip of his fishing rod; the pine scent wafting through the screens; and early morning paddles “when the lake was cool and motionless.” Although some things had changed, much remained as he remembered—so much so that he had a few confused moments, uncertain if he was the father or the child.

Lakes stay with you.

When I was seventeen, a boy gave me a book of poetry by W.B. Yeats. The poem I loved most was “The Lake Isle of Innisfree,” penned more than a century ago in Ireland. The author was a young man in his twenties—but his poem is filled with nostalgia and longing. Living in London and yearning for a more peaceful place and time, he begins, “I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree.”

Innisfree is a real place. As a child, the poet often visited this small island in Lough Gill with his family. Whether in reality or in memory, he always returned to the lake.

I divide my life into three lakes: my original one, where I lived with my parents and my brother; the Maine lake where I taught my own children to swim and skip stones; and my current one, a small New Hampshire lake with long stretches of undeveloped shoreline. I spend early morning and dusk with the birds—cedar waxwings, nuthatches, woodpeckers, titmice, robins—as they work the alders and huckleberries.

Directly across the lake is a Girl Scout camp with a small waterfront. The voices of the campers are as welcome as those of the birds, as they play Marco Polo, cruise along the shore on paddleboards and set out on their cross-lake swims accompanied by counselors in kayaks. Each twoweek stay ends with a ceremony on the beach, beginning at dusk and lasting until well after dark. After the last campfire song, each Scout lights a candle and carries it to her cabin. Tiny white lights weave through the trees in a line and gradually disappear as the girls go inside to their bunks. The lake will always belong to them. NHH